|

I received 78 credits on The Sci Fi Sounds Quiz How much of a Sci-Fi geek are you? |

| Take the Sci-Fi Movie Quiz canon s5 is | |

Archive for Movies & TV

Supergeek!

Racist Comedy Gaze

So I watched some standup comedy special on Comedy Central. It was a couple of weeks old, but I have a DVR, so there you go. It was a single live performance featuring Dave Attell, D.L. Hughley, and Lewis Black. They performed their routines in that order, and then came out and did a thing together.

At some point, I became aware of the way the camera moved through the audience. You know what I mean; the audience members laughing in response to something the comedian has said.

Everyone shown in the audience for the white comedians was white. Everyone shown in response to Hughley was black.

I don’t get it. I mean, what’s the purpose of that? Is it scary to show white people enjoying Hughely? Does that provoke white anxiety in some way that eludes me? Are Black and Attell so unfunny to blacks that it would be implausible to show black audience members laughing at them? Are the camera operators, incredible as it seems, unaware that they are making racial choices?

There’s certainly a quantity of racial content in any comedian’s routine. Hughley does humor that is more black, Black does humor that is specifically Jewish (and Attell just isn’t fucking funny). And none of that feels racist or problematic. But the audience stuff; I had a real problem with that, and I just. Don’t. Get it.

Monday Movie Review: Once

Once (2007) 10/10

A Dublin busker (Glen Hansard) meets an Eastern European girl (Markéta Irglová) and they form a friendship that changes both of them. (The IMDb lists this as a 2006 movie, but the awards and such are listing it as 2007.)

I kind of wonder what a professional critic does when confronted by the “nothing much happens” kind of movie. Once is extraordinarily simple, to the point where it almost defies description, yet any reviewer would want to describe it, inasmuch as a description might persuade someone to see it, and it’s worth seeing. But why? Ah, there’s the rub.

The unnamed guy (Hansard) works in his father’s vacuum cleaner repair shop and sings on the street. By day he sings popular tunes to earn tips from passers-by; by night he sings his heartfelt originals. It is at night that the unnamed girl (Irglová) stops to talk to him. She has heard him during both day and night, and loves his original material. He is resistant to her conversation at first; he’s trying to play, not chat, but she is fascinated by him and persists in discussing music, finally getting under his skin by getting him to agree to fix her vacuum. She brings it the next day, and they discuss her own background as a pianist. The conversation is filmed as they walk; charmingly, she drags the vacuum along behind her like a bright blue puppy.

The movie is more than half musical performance, all in the context of musicians making music, and communicating their unspoken feelings through their music. There isn’t a direct lyrics-to-plot relationship; it’s more the level of intensity these people allow themselves is only available when they play, sing, and compose.

This isn’t a conventional romance. From the first, the girl recognizes that the guy’s songs are about a woman he hasn’t gotten over, and she encourages him to find her and win her back with his songs. Yet the friendship they have, as supportive and good and genuinely friendly as it is, seems constantly tinged with a longing to touch and love. Most of which is expressed simply in Hansards enormous blue eyes gazing at her, and Irglová’s delicate, careful turning away.

This is a low-budget film that looks like a home movie, and such films often annoy me. I don’t think looking cheap is a virtue, and I don’t like a shaky camera. But the camera doesn’t shake, and naturalism is the heart of this film; the naturalism of the music, of the characters, of the dialogue; it works perfectly.

What else can I say? The girl’s encouragement inspires the guy and allows him to want more and try for more than he’d dared before. Together they rent a studio to record a demo; neither would have achieved this without the other, but this is never spoken. How people react to the music is persistently delightful.

There are small Irish movies that are relentlessly charming. They whack you over the head with the charming sledge hammer. Look! We’re charming! See how quirky and Irish and quaint we are! Once has nothing in common with those movies; it’s populated by people, not quaint characters, and it is always true to itself.

I just realized…

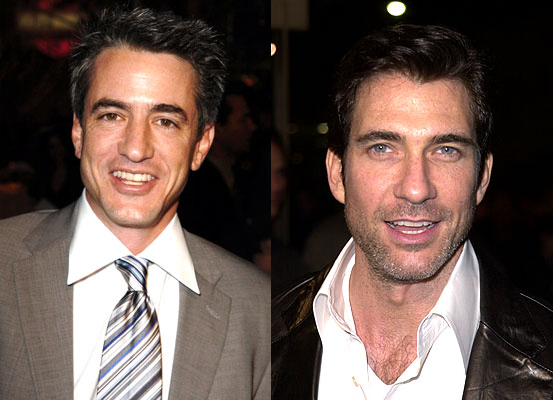

that I’ve been confusing Dermot Mulroney and Dylan McDermott forever. That’s why I never recognize whichever one is in whichever movie I see.

When I saw The Family Stone, I thought, how come I never realized that guy was so handsome? I didn’t think he was all that in Steel Magnolias! Yeah, I thought that.

Monday Movie Review: My Darling Clementine

My Darling Clementine (1946) 10/10

Wyatt Earp (Henry Fonda) and his brothers are passing their cattle through Tombstone when Billy Earp is murdered. Wyatt accepts an offer to become Marshall, and deputizes his surviving brothers, so that he can find the killer. Directed by John Ford.

I was excited when I saw this movie was going to be on; there’s a shrinking list of really acclaimed Westerns I have yet to see, and My Darling Clementine didn’t disappoint. It was as exquisitely beautiful as you’d expect a John Ford Western to be; masterfully filmed, every frame perfection. Ford captures all the subtle and broad, clumsy and graceful movements that add up to rich characters in a beautifully made movie. I think my favorite moment is this: Wyatt Earp has taken to sitting in front of the hotel, watching the town, leaned way back in a chair with one long leg up on a post in front of him. This is so much his habit that someone runs to get his chair when he sees Earp coming (itself a lovely touch). Then, in one scene, while thinking about taking the eponymous Clementine Carter to a dance, Earp stretches out his arms and, still leaning back in the chair, does dance steps on the post.

I could talk about the themes of this movie, about trying to reach past yourself, about finding beauty, all that, but to me, I’m pretty sure what I’m going to remember is that this is the movie where Henry Fonda danced on the post; a purely visual elegance.

My Darling Clementine also makes total hash of the historical fact. I have a book I like a lot called Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies. As the title suggests, it treats a host of movies with a historical basis to a comparison with the facts. The chapter on Wyatt Earp and the shootout at the OK Corral actually encompasses seven movies (although many more could have been included). Having read this book, and seen numerous other films with these characters, I was very aware of the factual errors. I mean, all movies stretch or strain fact somewhere, and Westerns more than most, but My Darling Clementine doesn’t even try! It ignores such basics as which Clantons and Earps were even at the OK Corral, who lived, and who died.

They’re arguing over the need for historical accuracy (or lack thereof) over on the IMDb message board for this film. Does accuracy matter when the film is so great? Or at all? If you don’t intend to be accurate, why use the names of historical figures and events at all? Ford knew Wyatt Earp, who hung around Hollywood at the end of his life, and would tell people that his portrayal of the events of the OK Corral was accurate because he heard about it from Earp himself. But then, when people complained about the inaccuracies, he fell back to “Well, did you enjoy the movie?”

All these arguments are interesting, but while you’re arguing, see My Darling Clementine, because it really is amazing.

Monday Movie Review: The Namesake

The Namesake (2006) 6/10

Ashoke Ganguli (Irfan Khan), a Bengali professor living in New York, marries Ashima (Tabu) and brings her to the United States in 1974. Their American-born son Gogol (Kal Penn) struggles between his family’s traditionalism and his desire to assimilate. Directed by Mira Nair.

The Namesake is a movie struggling to find itself. Although I haven’t read the novel, and so have no idea how close it is to its source, it feels like a movie trying to slavishly follow a novel’s plot and pacing. It has a novels way of rising and falling around events, without a clear flow of character or narrative arc. I wanted to take it apart, shake off the loose pieces, and put it back together with a more sound structure. Almost everything about the movie is appealing except its inability to tell a story.

This is the sort of movie I see all the time and don’t bother to write a full review of. (After all, most weeks I see two or three movies and only review one here.) But it has some very good qualities that are worth discussing. First, of course, is the modern immigrant experience; arriving not on Ellis Island but at JFK International Airport, treated symbolically (if clumsily) in the movie as a sort of waystation; each time the Ganguli family passes through JFK they pass between worlds; between states of being. Ashoke and Ashima are always aliens in their adopted country, their traditions don’t fit in. And looking at it, you can certainly see how most of our traditions didn’t fit in at one point, and how the first generation born here struggled with a foot in each world.

There’s a fascinating anti-feminist feminist component about The Namesake. I realize that sounds contradictory, so hang in there.

In the course of the movie, there are two women in Gogol’s life. They are incredibly poorly-written characters, stereotypes of Evil Feminists or Evil Modernism or something else Evil and Female. Their evils are variously independence, informality, premarital sex, wearing short skirts, and disrespecting tradition. The feeling at the end of the movie, when the family comes to a particular sort of resolution but the Evil Women are cast aside, is of misogyny.

Rethinking my position involves spoilers about the end. Continue at your own risk.

Monday Movie Review: The Hours

The Hours (2002) 10/10

A single, pivotal day in the lives of three women: Virginia Woolf (Nicole Kidman) in the 1920s as she writes Mrs. Dalloway; Clarissa Vaughan (Meryl Streep) in 2001, as she prepares to throw a party for her friend Richard (Ed Harris), whose nickname for her is Mrs. Dalloway, and Laura Brown (Julianne Moore) in the 1950s, who is reading Mrs. Dalloway.

Last week, I saw The Hours for the second time (I saw it in the theater in 2002), and then read the novel The Hours.

The first thing I should say is that The Hours is fully and one hundred percent a movie. What author Michael Cunningham did with words in his novel is done visually in the film. Director Stephen Daldry created a visual language, a language of jewelry and flowers and color and food. The women flow in and out of each other, and that’s crucial, but it’s not done in a way that’s verbal or linear. They connect in their hand movements, and their earrings; the visual particulars of life, every bit as much as they connect through events. This is what I think the movie’s great achievement is, to work from a famous and highly regarded novel, and not to succumb to novel-worship. The Hours is a story to look at and to feel.

The novel, on the other hand, is very much a story to read. Its words are exquisite, complex, delicate, and dense.

As she pilots her Chevrolet along the Pasadena Freeway, among hills still scorched in places from last year’s fire, she feels as if she’s dreaming or, more precisely, as if she’s remembering this drive from a dream long ago. Everything she sees feels as if it’s pinned to the day the way etherized butterflies are pinned to a board. Here are the black slopes of the hills dotted with the pastel stucco houses that were spared from the flames. Here is the hazy, blue-white sky…She is a woman in a car dreaming about being in a car.

This passage stuns me. It’s just Laura driving; but all the images add up to so much; to numbness and death and escaping death, to the beauty of life and the intense sense of disconnection.

Daldry achieves something similar in the film, although not quite as brilliantly. I don’t want to compare the two (that never works) so much as contrast them and use the novel to illuminate the movie, to show both its brilliance and its flaws. Certainly the internal life of each woman cannot be conveyed as easily on film. Instead, the movie is more emotional, more embracing. It’s a good choice. It’s a movie that makes you cry without being a “tearjerker.” Which is to say, I didn’t feel jerked.

Both times I saw the movie I was intensely struck by the costumes, by how put together they were, perfectly real in a way that was almost too perfect. Clarissa dresses exactly like the character she is; a successful New York lesbian with a long-time partner and a gorgeous brownstone. The black turtleneck, the elaborate necklace, the amber earrings, all just so. And the book definitely gave me insight into that; each woman is aware that she’s performing; Laura Brown just doesn’t dream she’s a woman driving, she is playing the character of a woman driving, of a pregnant housewife and a mother baking a cake. The heightened tone illustrates that.

There are sour notes in the movie. There were lines that felt so “literary adaptation,” that were so written. And they fell with a thud. Interestingly, those lines mostly weren’t in the book; they were an attempt to convey things from the book in dialogue rather than in imagery and action. Screenwriter David Hare is the likely culprit; he’s better known as a playwright than a screenwriter, and the literary tone could certainly work on the stage.

Ed Harris is kind of off. His dialogue didn’t fit his emotional presence. I understood the character much better reading him; in the novel he was kind of fey, but Harris plays Richard with a driving rage, and that doesn’t entirely work.

But these are isolated moments. The movie is completely worth seeing, completely fascinating. So few movies attend to the small details of life in a way that adds up to something larger. The Hours is one of them.

Monday Movie Review: Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead

Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007) 9/10

Hank (Ethan Hawke) and Andy (Philip Seymour Hoffman) are brothers. For their own reasons, each is desperate for money. Together they decide to commit the perfect crime—rob their parents’ small suburban jewelry store. As things fall apart, the brothers become increasingly desperate, and more and more of their motivations and characters are revealed. Directed by Sidney Lumet.

Nowadays, movie fans are obsessive about continuity and plot holes. I honestly don’t think Hitchcock would get the raves today he got in his heyday, because people would walk out of the theater griping. “That’d never happen!” “Why didn’t he…?” “Police procedure would require…” Yada yada yada. So let’s start out by saying that Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead has plot holes. Some of them are problematic, and detract from the enjoyment of the film. But BtDKYD is also a brilliant movie, and you shouldn’t let a few details get in the way of your experience.

I bring this up because BtDKYD is a heist movie, and a heist movie demands more attention to plot construction than, say, a romance. This week I also watched The Killing, another heist movie in which everything falls apart. But The Killing is flawlessly constructed. None of the heist movies that I love (and I love many) have glaring plot holes; good construction is important to the genre.

But is BtDKYD really a heist movie? One could argue that it is a noir, a family story, or a character study. The heist guides us into an examination of complex and difficult people. We learn more about them, hating them more and more as the film goes on, yet paradoxically caring more and more about what happens to them.

Hank is a loser. Everything about him screams it: His ill-fitting, cheap clothes, his cheesy mustache, his sad-sack expression. He allows himself to be brow-beaten by his older brother, and it’s clear he’s been doing so his whole life. Hank is clearly the charmer of the family, perhaps taking after his mother’s clear-eyed beauty (she is played with great dignity by Rosemary Harris). He is the pampered, beautiful baby, getting by on looks where common sense and brains are lacking. Andy, on the other hand, is shrewd and calculating, apparently his father’s son (and Albert Finney is a good choice, physically, to play Hoffman’s father).

Wonderful cast, right? I have been complaining lately about the unworldly beauty of every single person you see on a large or small screen. The real faces and ages of actors are disappearing. But not only do the people in this cast have real character, they are allowed to age. Hoffman’s wife is played by Marisa Tomei, who is actually three years older than him. When was the last time that happened in a movie?

Lumet is a master of knowing where to place a camera and what to do with it once he gets it there. There are amazing things done with color and light in this film. In a disturbing scene, Andy begins to reveal himself in the most inappropriate way, as a white background is replaced by red. The suburban stripmall that houses the jewelry store is as ordinary as a home movie. Hank’s cheap apartment is washed in the colors of dirt.

There is something in BtDKYD about wasted lives, about how we keep being the assholes we are, and about how we can spin that so it gets worse and worse and worse. Andy and Hank are assholes, no doubt. They are shitty husbands, dishonest sons, crooks, theives, and not even good brothers. But we relate to them because they look at the mess their lives are in and long to get out, and they look to their own family to help them. It won’t work, of course, but the insanity of the longing is compelling.

Monday Movie Review: Seraphim Falls

Seraphim Falls (2006) 5/10

A trapper named Gideon (Pierce Brosnan) is shot by Carver, a man from his past (Liam Neeson), seeking to settle an unknown grudge from the Civil War.

Most of Seraphim Falls is Neeson’s pursuit of Brosnan, and Brosnan’s desperate flight of survival. Shot in the shoulder, he barely uses the arm at all for the length of the film, and the pursuit and flight have a brutal sort of realism. The cinematography is iconically Western, and enjoyable. Dialogue is sparse. Brosnan is almost entirely alone; Neeson interacts with the men he has hired to help him in his pursuit, but there’s nothing in the way of musing about the past or swapping yarns or anything like that. These men embody the laconic Western anti-hero, and we watch with interest. Unable to determine right or wrong, we let our sympathies fall in the middle. Brosnan makes the interesting choice of gasping and crying out in pain as he flees from his (at that time) unknown shooter; he’s tough as they come, so you expect a typical macho stoicism. He doesn’t have it. He’s hard, he’s smart, he’s an incredible survivor, but he gasps and cries out and weeps. Meanwhile, Neeson is relentless and single-minded. Thus, your sympathy moves towards Brosnan. At the same time, you definitely are aware that Neeson has some good reason for his vendetta, that he feels he is the wronged party. This isn’t some villain out to avenge some villainous deed.

There’s no doubt, as you watch this very silent, beautifully bare movie, that the explanation will only come when the two at last meet. And indeed, this is what happens. Unfortunately, the back story we’re given, after all that wait, is merely okay. It answers some questions but is bare in places it should not be. It skews towards making Neeson’s character too much the cliché of sweetness and light. But okay, it was a good-looking movie, appealingly tough, and I was willing to have a back story, an ending, and call it a night.

But no.

Shortly before the final showdown, there were a couple of scenes with a group of pilgrims that made no sense to me. They felt strangely episodic, and reminded me of Dead Man. (I never want to be reminded of Dead Man.)

Turned out that was a prophetic reminder. After what I thought was the film’s denouement, it keeps going. Only now it’s mystical. That’s right, the gritty realism gives way to sudden appearances by characters speaking cryptically with pseudo-wisdom. And one of them is Anjelica Huston. There’s a lot of that. If there was a little, I’d be like, Oh this is a good movie that I recommend, but ignore the ending. But the ending isn’t the ending, it’s approximately the final third of the movie. And that’s just wrong.

After I endured all this nonsense, Arthur pointed out that “seraphim” is, itself, a mystical term; seraphim are the many-eyed angels who sit beside God in heaven. So “Seraphim Falls” = Fallen Angels. What. Ev. Er.

Look. People. I mean you, you movie-making people. Make a good movie with meaning. Don’t structure a meaning and then shoehorn the movie into it. Don’t assume your audience is so numb to meaning that we can’t tell there’s any in your film unless you broadcast it with neon This! Is! The! Meaning! signs.

It’s your fault you made me take most of the points away from this movie. Meet me halfway, people.

Wicca on House

House is one of my favorite TV shows. Even when it’s a bad episode, I enjoy it. Last night, there was a mention of Wicca on House, and I thought it was notable.

There’s a film crew doing a documentary about one of House’s patients. They interview Wilson (Robert Sean Leonard) who uses the opportunity to totally punk his best friend, House. He does a whole song and dance about how “the records were sealed” and “he was probably just tapping his toes” and then says “it was a witch hunt” and the documentarians asked if he means House was singled out because…And Wilson interrupts and says “No, I mean literally. House practices the religion of Wicca. It’s a beautiful religion, all about love. They’re very sweet people.”

Okay, if you know what an evil cynic House is, it’s hysterically funny. But notice that (a) What Wilson said about Wicca was positive and nice and fairly accurate, (b) His usage was correct—not “House is a Wicca” like they were always saying on Buffy, but “the religion of Wicca,” and (c) the joke only works if a familiarity with Wicca can be assumed in the audience. And yes, that familiarity includes being bemused and thinking it’s silly—fluffy—but I still think it’s huge progress.